Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston

Island Universe / Josiah McElheny

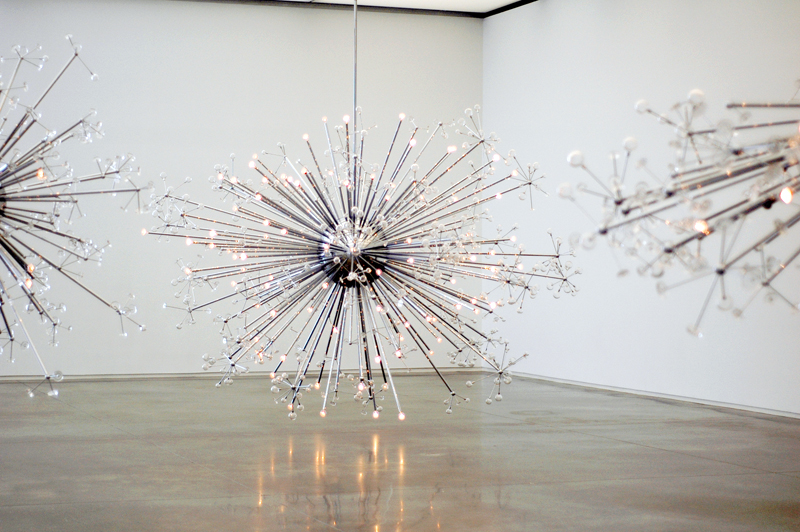

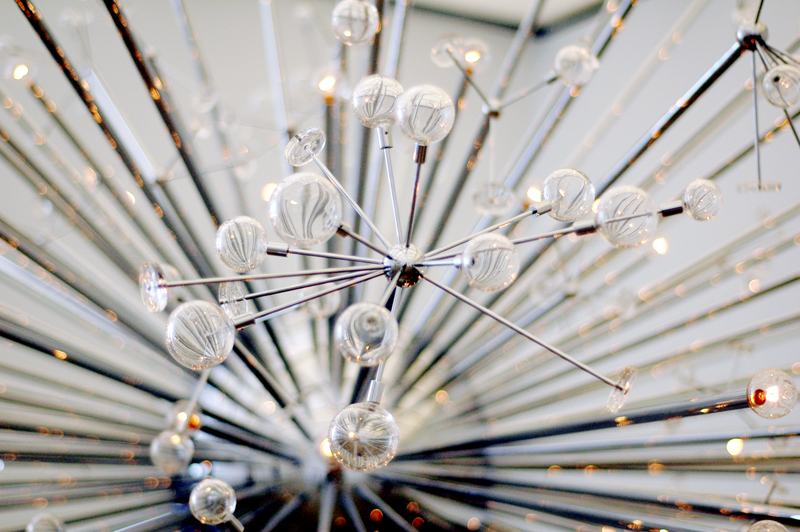

Held aloft at varying heights, five glittering sculptures form a silvery constellation.While each of Island Universe’s dangling structure sis unique in composition and dimensions, all are comprised of the same elements: chrome-plated sphere sprouting metal rods capped with lightbulbs or circles of glass. The sculptures’ distinctive forms are derived from the J. & L. Lobmeyr chandeliers at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, but McElheny invests these icons of mid-century design with a wealth of scientific data. When first confronted with these ornamental fixtures, he immediately connected them to renderings of the Big Bang, but hoped to take that link beyond visual similarity. “What if I remade the chandeliers,” he asked himself, “so that instead of it being a glass on the theory, all of the decisions were determined by the actual science of the origin of the universe?”

Held aloft at varying heights, five glittering sculptures form a silvery constellation.While each of Island Universe’s dangling structure sis unique in composition and dimensions, all are comprised of the same elements: chrome-plated sphere sprouting metal rods capped with lightbulbs or circles of glass. The sculptures’ distinctive forms are derived from the J. & L. Lobmeyr chandeliers at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, but McElheny invests these icons of mid-century design with a wealth of scientific data. When first confronted with these ornamental fixtures, he immediately connected them to renderings of the Big Bang, but hoped to take that link beyond visual similarity. “What if I remade the chandeliers,” he asked himself, “so that instead of it being a glass on the theory, all of the decisions were determined by the actual science of the origin of the universe?”

Working in collaboration with the cosmologist David Weinberg, McElheny fashioned a system to represent our ever-expanding universe, converting the almost inconceivable span of cosmic distance into visual depictions of current scientific theories. The five hanging structures represent different models of the cosmos, following the Multiverse theory of Andrei Linde, which proposes the coexistence of many potential universes, each with its own unique shape and properties. The sculptures’ parts correspond to specific astronomical realities, with the handblown glass globes and discs representing clusters of galaxies, and the lightbulbs signifying quasars.

As we approach these suspended sculptures, their polished cores reflect our image, placing us firmly at the center of the work but shrunk to miniature proportions. The overwhelming scale of Island Universe prompts reflection on the enormity of the universe and our tiny but crucial place within it.

Held aloft at varying heights, five glittering sculptures form a silvery constellation.While each of Island Universe’s dangling structure sis unique in composition and dimensions, all are comprised of the same elements: chrome-plated sphere sprouting metal rods capped with lightbulbs or circles of glass. The sculptures’ distinctive forms are derived from the J. & L. Lobmeyr chandeliers at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, but McElheny invests these icons of mid-century design with a wealth of scientific data. When first confronted with these ornamental fixtures, he immediately connected them to renderings of the Big Bang, but hoped to take that link beyond visual similarity. “What if I remade the chandeliers,” he asked himself, “so that instead of it being a glass on the theory, all of the decisions were determined by the actual science of the origin of the universe?”

Held aloft at varying heights, five glittering sculptures form a silvery constellation.While each of Island Universe’s dangling structure sis unique in composition and dimensions, all are comprised of the same elements: chrome-plated sphere sprouting metal rods capped with lightbulbs or circles of glass. The sculptures’ distinctive forms are derived from the J. & L. Lobmeyr chandeliers at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, but McElheny invests these icons of mid-century design with a wealth of scientific data. When first confronted with these ornamental fixtures, he immediately connected them to renderings of the Big Bang, but hoped to take that link beyond visual similarity. “What if I remade the chandeliers,” he asked himself, “so that instead of it being a glass on the theory, all of the decisions were determined by the actual science of the origin of the universe?”

Working in collaboration with the cosmologist David Weinberg, McElheny fashioned a system to represent our ever-expanding universe, converting the almost inconceivable span of cosmic distance into visual depictions of current scientific theories. The five hanging structures represent different models of the cosmos, following the Multiverse theory of Andrei Linde, which proposes the coexistence of many potential universes, each with its own unique shape and properties. The sculptures’ parts correspond to specific astronomical realities, with the handblown glass globes and discs representing clusters of galaxies, and the lightbulbs signifying quasars.

As we approach these suspended sculptures, their polished cores reflect our image, placing us firmly at the center of the work but shrunk to miniature proportions. The overwhelming scale of Island Universe prompts reflection on the enormity of the universe and our tiny but crucial place within it.

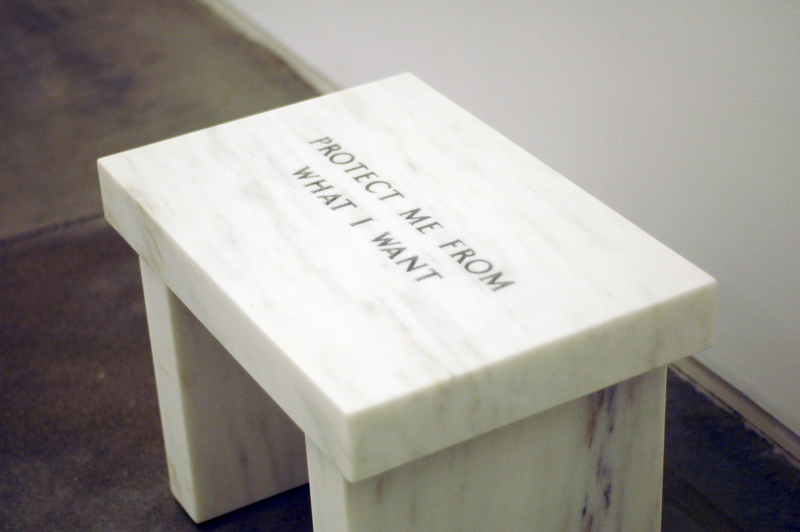

Survival: Protect Me from What I Want, 2006 / Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer is known for text-based works addressing themes of violence, sex, power, and history. Like other artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, Holzer borrows strategies from mass media and advertising. Reminiscent of memorial benches sometimes found in public parks, this small marble footstool has been etched with the words “protect me from what I want,” a phrase from Holzer’s series Survival (1983-85). Like much of Holzer’s work, the sculpture raises questions about the many forms of desire, from the lust for consumer goods to the longing for renown or immortality. Typically associated with classical statuary, gravestones, and tombs, marble transforms the humble footstool into a monument and lends a weighty permanence to its epitaph-like inscription.

Jenny Holzer is known for text-based works addressing themes of violence, sex, power, and history. Like other artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, Holzer borrows strategies from mass media and advertising. Reminiscent of memorial benches sometimes found in public parks, this small marble footstool has been etched with the words “protect me from what I want,” a phrase from Holzer’s series Survival (1983-85). Like much of Holzer’s work, the sculpture raises questions about the many forms of desire, from the lust for consumer goods to the longing for renown or immortality. Typically associated with classical statuary, gravestones, and tombs, marble transforms the humble footstool into a monument and lends a weighty permanence to its epitaph-like inscription.

Jenny Holzer is known for text-based works addressing themes of violence, sex, power, and history. Like other artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, Holzer borrows strategies from mass media and advertising. Reminiscent of memorial benches sometimes found in public parks, this small marble footstool has been etched with the words “protect me from what I want,” a phrase from Holzer’s series Survival (1983-85). Like much of Holzer’s work, the sculpture raises questions about the many forms of desire, from the lust for consumer goods to the longing for renown or immortality. Typically associated with classical statuary, gravestones, and tombs, marble transforms the humble footstool into a monument and lends a weighty permanence to its epitaph-like inscription.

Jenny Holzer is known for text-based works addressing themes of violence, sex, power, and history. Like other artists who came to prominence in the 1980s, Holzer borrows strategies from mass media and advertising. Reminiscent of memorial benches sometimes found in public parks, this small marble footstool has been etched with the words “protect me from what I want,” a phrase from Holzer’s series Survival (1983-85). Like much of Holzer’s work, the sculpture raises questions about the many forms of desire, from the lust for consumer goods to the longing for renown or immortality. Typically associated with classical statuary, gravestones, and tombs, marble transforms the humble footstool into a monument and lends a weighty permanence to its epitaph-like inscription.

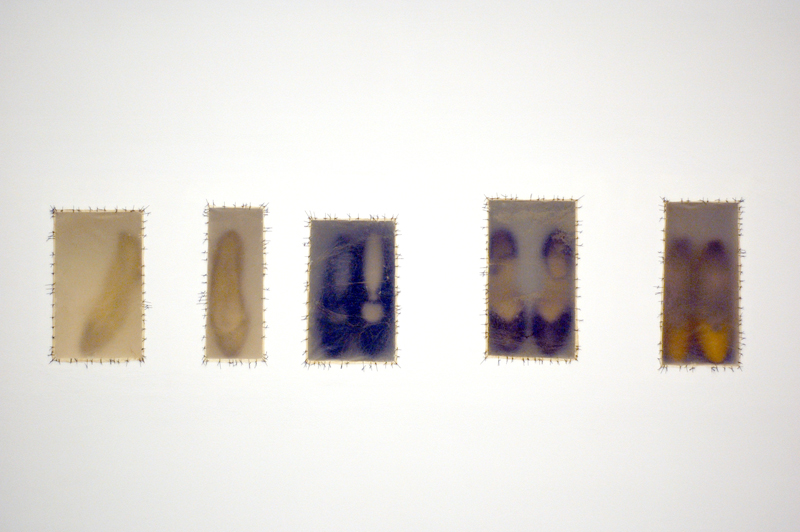

Atrabiliarios, 1996 / Doris Salcedo

The title Atrabiliarios references the Latin expression atra bilis, which describes a sense of melancholy associated with mourning. Here worn shoes are inserted directly into the gallery wall and covered with stretched cow bladder. This skin-like membrane is coarsely sewn to the wall with surgical thread, creating a milky layer between the viewer and the discarded shoes. Salcedo collected the shoes from the families of los desaparecidos, people, mainly women, who have been mysteriously “disappeared” from their homes, a method of social control commonly practiced in Colombia in the midst of the internal conflict between paramilitary and guerilla forces in the 1980s. Now discarded, the once lived-in shoes offer a metaphor for the body’s absence, a specter of loss and death summoned further by the sewn “skin” that encloses them, calling to mind post-autopsy stitching.

The title Atrabiliarios references the Latin expression atra bilis, which describes a sense of melancholy associated with mourning. Here worn shoes are inserted directly into the gallery wall and covered with stretched cow bladder. This skin-like membrane is coarsely sewn to the wall with surgical thread, creating a milky layer between the viewer and the discarded shoes. Salcedo collected the shoes from the families of los desaparecidos, people, mainly women, who have been mysteriously “disappeared” from their homes, a method of social control commonly practiced in Colombia in the midst of the internal conflict between paramilitary and guerilla forces in the 1980s. Now discarded, the once lived-in shoes offer a metaphor for the body’s absence, a specter of loss and death summoned further by the sewn “skin” that encloses them, calling to mind post-autopsy stitching.

“When a person disappears, everything becomes impregnated with that person’s presence. Every single object as well as every space is a reminder of that person’s absence, as if absence were stronger than presence.”

Born and raised in Bogota, Colombia, where she currently lives and works, Doris Salcedo is an artist of international renown. Since the mid-1980s her work has addressed loss and mourning, bearing witness to the universal effects of criminal and political violence. Salcedo’s sculptures and installations are informed by her research and extensive fieldwork in rural communities in Colombia, particularly by the testimonies she collects from survivors and the families of those who have disappeared and are presumed dead. Her work both honors the memory of lives lost and contemplates the frequently silent nature of trauma.

Salcedo employs an uncomfortable combination of domestic furniture and building materials such as concrete and steel, by distorting the familiar her work transforms our sense of home from a space of comfort and safety to one of disorienting dislocation. Instead of engaging the traditional methods of sculpture, such as carving or molding, she makes her work through acts of physical and symbolic violence: filing, scratching, bending, beating, fusing, melting, and burying. Her sculptures are visual manifestations of violence, suffering, and loss.

The title Atrabiliarios references the Latin expression atra bilis, which describes a sense of melancholy associated with mourning. Here worn shoes are inserted directly into the gallery wall and covered with stretched cow bladder. This skin-like membrane is coarsely sewn to the wall with surgical thread, creating a milky layer between the viewer and the discarded shoes. Salcedo collected the shoes from the families of los desaparecidos, people, mainly women, who have been mysteriously “disappeared” from their homes, a method of social control commonly practiced in Colombia in the midst of the internal conflict between paramilitary and guerilla forces in the 1980s. Now discarded, the once lived-in shoes offer a metaphor for the body’s absence, a specter of loss and death summoned further by the sewn “skin” that encloses them, calling to mind post-autopsy stitching.

The title Atrabiliarios references the Latin expression atra bilis, which describes a sense of melancholy associated with mourning. Here worn shoes are inserted directly into the gallery wall and covered with stretched cow bladder. This skin-like membrane is coarsely sewn to the wall with surgical thread, creating a milky layer between the viewer and the discarded shoes. Salcedo collected the shoes from the families of los desaparecidos, people, mainly women, who have been mysteriously “disappeared” from their homes, a method of social control commonly practiced in Colombia in the midst of the internal conflict between paramilitary and guerilla forces in the 1980s. Now discarded, the once lived-in shoes offer a metaphor for the body’s absence, a specter of loss and death summoned further by the sewn “skin” that encloses them, calling to mind post-autopsy stitching.

“When a person disappears, everything becomes impregnated with that person’s presence. Every single object as well as every space is a reminder of that person’s absence, as if absence were stronger than presence.”

Born and raised in Bogota, Colombia, where she currently lives and works, Doris Salcedo is an artist of international renown. Since the mid-1980s her work has addressed loss and mourning, bearing witness to the universal effects of criminal and political violence. Salcedo’s sculptures and installations are informed by her research and extensive fieldwork in rural communities in Colombia, particularly by the testimonies she collects from survivors and the families of those who have disappeared and are presumed dead. Her work both honors the memory of lives lost and contemplates the frequently silent nature of trauma.

Salcedo employs an uncomfortable combination of domestic furniture and building materials such as concrete and steel, by distorting the familiar her work transforms our sense of home from a space of comfort and safety to one of disorienting dislocation. Instead of engaging the traditional methods of sculpture, such as carving or molding, she makes her work through acts of physical and symbolic violence: filing, scratching, bending, beating, fusing, melting, and burying. Her sculptures are visual manifestations of violence, suffering, and loss.

Czech Modernism Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely / Josiah McElheny

Inside a mirrored vitrine, eight lidded decanters stand in a regimented row, their forms echoed behind them in infinite lines of perfect copies. Despite the brilliant clarity of this mirror-on-mirror, the spectator’s body is not reflected, creating a disorienting sense of exclusion. Czech Modernism mines the darker side of modernity, its static forms depicting what the artist calls “the horror of endlessly repeated production,” in which the world of mass-produced objects mirrors our similarities while ignoring our differences.

Inside a mirrored vitrine, eight lidded decanters stand in a regimented row, their forms echoed behind them in infinite lines of perfect copies. Despite the brilliant clarity of this mirror-on-mirror, the spectator’s body is not reflected, creating a disorienting sense of exclusion. Czech Modernism mines the darker side of modernity, its static forms depicting what the artist calls “the horror of endlessly repeated production,” in which the world of mass-produced objects mirrors our similarities while ignoring our differences.

Inside a mirrored vitrine, eight lidded decanters stand in a regimented row, their forms echoed behind them in infinite lines of perfect copies. Despite the brilliant clarity of this mirror-on-mirror, the spectator’s body is not reflected, creating a disorienting sense of exclusion. Czech Modernism mines the darker side of modernity, its static forms depicting what the artist calls “the horror of endlessly repeated production,” in which the world of mass-produced objects mirrors our similarities while ignoring our differences.

Inside a mirrored vitrine, eight lidded decanters stand in a regimented row, their forms echoed behind them in infinite lines of perfect copies. Despite the brilliant clarity of this mirror-on-mirror, the spectator’s body is not reflected, creating a disorienting sense of exclusion. Czech Modernism mines the darker side of modernity, its static forms depicting what the artist calls “the horror of endlessly repeated production,” in which the world of mass-produced objects mirrors our similarities while ignoring our differences.

South of No North, 1995 / Collier Schorr

Collier Schorr has photographed teenagers across Germany and the United States since the early 1990s. Her subjects project casual self-assurance; their gazes are unflinching. In this calm, however, the volatile uncertainties of adolescence are still present. Her titles conjure sensual daydreams. Even the high-contrast saturation of the color seems hormonal. Schorr’s work addresses the desires and conflicts that attend the social construction of gender (especially masculinity). Her photographs display an interest in androgyny. In her larger oeuvre, the refusal of the binary logical of girl/boy extends to other social and historical oppositions, such as German nationalism and Jewish identity. Schorr’s pictures are disarming partly because they feel so intimate; her subjects could be a neighbor, brother, or friend.

Collier Schorr has photographed teenagers across Germany and the United States since the early 1990s. Her subjects project casual self-assurance; their gazes are unflinching. In this calm, however, the volatile uncertainties of adolescence are still present. Her titles conjure sensual daydreams. Even the high-contrast saturation of the color seems hormonal. Schorr’s work addresses the desires and conflicts that attend the social construction of gender (especially masculinity). Her photographs display an interest in androgyny. In her larger oeuvre, the refusal of the binary logical of girl/boy extends to other social and historical oppositions, such as German nationalism and Jewish identity. Schorr’s pictures are disarming partly because they feel so intimate; her subjects could be a neighbor, brother, or friend.

Collier Schorr has photographed teenagers across Germany and the United States since the early 1990s. Her subjects project casual self-assurance; their gazes are unflinching. In this calm, however, the volatile uncertainties of adolescence are still present. Her titles conjure sensual daydreams. Even the high-contrast saturation of the color seems hormonal. Schorr’s work addresses the desires and conflicts that attend the social construction of gender (especially masculinity). Her photographs display an interest in androgyny. In her larger oeuvre, the refusal of the binary logical of girl/boy extends to other social and historical oppositions, such as German nationalism and Jewish identity. Schorr’s pictures are disarming partly because they feel so intimate; her subjects could be a neighbor, brother, or friend.

Collier Schorr has photographed teenagers across Germany and the United States since the early 1990s. Her subjects project casual self-assurance; their gazes are unflinching. In this calm, however, the volatile uncertainties of adolescence are still present. Her titles conjure sensual daydreams. Even the high-contrast saturation of the color seems hormonal. Schorr’s work addresses the desires and conflicts that attend the social construction of gender (especially masculinity). Her photographs display an interest in androgyny. In her larger oeuvre, the refusal of the binary logical of girl/boy extends to other social and historical oppositions, such as German nationalism and Jewish identity. Schorr’s pictures are disarming partly because they feel so intimate; her subjects could be a neighbor, brother, or friend.

Takaho after kissing, Tokyo, 1994 / Nan Goldin

Since the 1970s, Nan Goldin has made candid photographs of her friends and family, creating a “visual diary” of her live. Visiting Tokyo in the early 1990s, Goldin was struck by the beauty of the city and its people, and for the first time photographed strangers, on the streets and in the clubs, to produce the series Tokyo Love. As Goldin recalls: I met kids who were so like my own friends and I were in our late teens. I found a household of kids who are living by the same beliefs that I did as a teenager, and who have transcended any definitions of the hetero or homosexual. I was deeply touched, I fell in love with face after face.

Since the 1970s, Nan Goldin has made candid photographs of her friends and family, creating a “visual diary” of her live. Visiting Tokyo in the early 1990s, Goldin was struck by the beauty of the city and its people, and for the first time photographed strangers, on the streets and in the clubs, to produce the series Tokyo Love. As Goldin recalls: I met kids who were so like my own friends and I were in our late teens. I found a household of kids who are living by the same beliefs that I did as a teenager, and who have transcended any definitions of the hetero or homosexual. I was deeply touched, I fell in love with face after face.

Golding captures these young adults in intimate settings. Her signature hand-held close-up shots show the details of youths constructing identity through costumes and makeup they have seen on MTV and in fashion magazines.

Since the 1970s, Nan Goldin has made candid photographs of her friends and family, creating a “visual diary” of her live. Visiting Tokyo in the early 1990s, Goldin was struck by the beauty of the city and its people, and for the first time photographed strangers, on the streets and in the clubs, to produce the series Tokyo Love. As Goldin recalls: I met kids who were so like my own friends and I were in our late teens. I found a household of kids who are living by the same beliefs that I did as a teenager, and who have transcended any definitions of the hetero or homosexual. I was deeply touched, I fell in love with face after face.

Since the 1970s, Nan Goldin has made candid photographs of her friends and family, creating a “visual diary” of her live. Visiting Tokyo in the early 1990s, Goldin was struck by the beauty of the city and its people, and for the first time photographed strangers, on the streets and in the clubs, to produce the series Tokyo Love. As Goldin recalls: I met kids who were so like my own friends and I were in our late teens. I found a household of kids who are living by the same beliefs that I did as a teenager, and who have transcended any definitions of the hetero or homosexual. I was deeply touched, I fell in love with face after face.

Golding captures these young adults in intimate settings. Her signature hand-held close-up shots show the details of youths constructing identity through costumes and makeup they have seen on MTV and in fashion magazines.

<< NEWER OLDER >>